The Delusion of Porn’s Harmlessness

An op-ed in the New York Times and reprinted in the NZ Herald this week points to a cultural tipping point. Those who argued that pornography did no harm are now admitting that they might be wrong.

Back in 2013 we alerted you to a book “Into the River” that had won the prestigious New Zealand Post Children’s Book Award – a book, according to the NZ Herald, laced with detailed descriptions of sex acts, the coarsest language and scenes of drug-taking, and which polarised the literary community? The book uses expletives including the c-word, depicts drug use and sex scenes, including one where a baby mimics sounds of intercourse. The Herald on Sunday even decided not to print extracts as they would offend some readers.

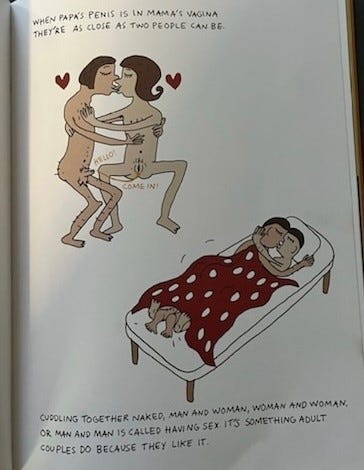

And then more recently we told you about a 9 year old child – in New Zealand – who was shown this book by another child in the library area. If she can see it that means 5 year olds can also see it. The book is How do you make a baby by Anna Fiske. Let’s have a look in the book – and let me warn you – this material is explicit and you may find it offensive.

Remember this is a book targeted at 5 years and up – and could be in your school library for your child to read.

And a McBlog in 2023 featuring Knox Zajac, an 11–year-old, in the US who spoke up at a school board meeting recently to read aloud from the illustrated romance for teenagers, “Nick and Charlie,” that he had checked out of his school’s library. The story begins with two early teen boys stealing wine from their parents and proceeding to experiment sexually with one another.

Two years ago the American Library Association released a list a couple of weeks ago of the 13 most “challenged” books aimed at teens during 2022, blaming anti-LGBT prejudice for what it calls censorship

The problem is that each book contains sexually explicit content. And other good reasons you wouldn’t want your children reading them. It’s not prejudice. It’s not anti LGBT.

It’s protecting young people from explicit, age-inappropriate, offensive and potentially upsetting material.

But the American Library Association encourages readers to “show your commitment to the freedom to read” by protecting the 13 books

Let’s look at the top books on the American Library Association’s list of 13 most-challenged books are:

1. ‘Gender Queer’ “Gender Queer” is a memoir written by nonbinary author Maia Kobabe, who prefers the pronouns “e/em/eir.” It has ranked as the ALA’s most banned book two years in a row because of its sexually explicit descriptions and illustrations. In one passage, Kobabe writes about trying to figure out if she is a gay boy trapped in a girl’s body, or whether a third, nonbinary option exists.

It includes graphic depictions of minors engaging in sexual intercourse including oral sex – a book that could be mistaken for a how-to manual. It also talks about girls wanting to be boys wearing chest binders and getting top surgery. It does in fact show drawings of a sexual encounter between a man and a young boy.

It is highly offensive. Yes I have read it. You do not want your child anywhere near this book

2. ‘All Boys Aren’t Blue’ “All Boys Aren’t Blue” has been removed from libraries in at least 29 school districts in the US because of parental concerns about “sexually graphic material, including descriptions of queer sex,” Time magazine reported.

3. ‘The Bluest Eye’ “The Bluest Eye” contains “sexually explicit material,” “lots of graphic descriptions and lots of disturbing language,” PBS writes, as well as “an underlying socialist-communist agenda.”

4. ‘Flamer’ “Flamer” includes graphic descriptions of LGBT relationships.

5. ‘Looking for Alaska’ and ‘The Perks of Being a Wallflower’

The books “Looking for Alaska” and “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” tied for fifth place on the library group’s list. They too include graphic descriptions, sexual abuse, drug use, profanity

Next on the American Library Association’s list of 13 most-challenged books is “Lawn Boy,” which reviewers say is a “pedophilic” work with “exploitative and abusive elements [that] go beyond the swear words and the sexual passages.” It describes oral sex between two ten-year-old boys.

Let me stop there.

You can see that pornographic material has long left the domain of just adults – and is being targeted not only at teenagers but also at very young children.

For far too long, we have been persuaded by the left - and the libertarians on the right - that pornography does no harm – that it’s consenting – that to object to it means you’re a prude – and to get with the sexual revolution.

And that it does no harm to children.

And the notion of faithfulness in marriage and one sexual partner for life is just so ‘yesterday’.

Here’s the interesting thing.

The very people who said that are now rethinking their stance – and admitting that maybe…. WE WERE RIGHT.

There’s an article reprinted in the NZ Herald but originally from the New York Times

In the introduction it says:

Despite significant evidence that a deluge of pornography has a negative impact on modern society, there is a curious refusal to publicly admit disapproval of it, writes Christine Emba.

I want to read some extracts from the article.

Now Christine Emba is a Catholic, and is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where her work focuses on gender and sexuality, feminism, masculinity, youth culture, and social norms. She is concurrently a contributing writer at The New York Times, has written for The Atlantic, was a columnist and editor at The Washington Post and was named one of the world’s top-50 thinkers by Prospect magazine in 2022. She is the author of Rethinking Sex: A Provocation (2022) which challenged today’s modern sexual ethics.

But it’s fascinating that the New York Times – no bastion of conservatism – has published this piece.

She writes:

These days, virality is difficult to achieve. But the British OnlyFans creator Lily Phillips managed it this winter, when she appeared in a documentary titled I Slept With 100 Men in One Day.

The film (available on YouTube in an edited form and unexpurgated on OnlyFans) followed Phillips as she planned for and executed the titular stunt, capturing everything from the shuffling feet of the men waiting outside her rented Airbnb to her shaken visage in the aftermath of the deed. (“It’s not for the weak girls,” she tells the filmmaker Josh Pieters, with tears in her eyes. “I don’t know if I’d recommend it.”)

Excessive? Certainly. Off-putting? To some. But perhaps not unexpected, if one considers how inured American society has become to women’s sexualisation and objectification – so much so that extremism seems like one of the few ways for an ambitious young sex worker to stand out.

She then gives the data on how pornography floods the internet.

A 2023 report from Brigham Young University estimated that pornography could be found on 12% of websites. Porn bots regularly surface on X, on Instagram, in comment sections and in unsolicited direct messages. Defenders of pornography tend to cite the existence of ethical porn, but that isn’t what a majority of users are watching. “The porn children view today makes Playboy look like an American Girl doll catalog,” one teenager wrote in 2023 in The Free Press, and it often has a focus on violence and dehumanisation of women. And the sites that supply it aren’t concerned with ethics, either. In a column last week, Nick Kristof exposed how Pornhub and its related sites profit off videos of child rape.

Speaking of that, one of our speakers at this year’s Forum on the Family is Dawn Hawkins who headed up a group that took on Pornhub. You need to hear what she has to say.

In her new book Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves, Sophie Gilbert critiques the mass culture of the 1990s and 2000s, noting how it was built on female objectification and hyperexposure. A generation of women, she explains, were persuaded by the ideas that bodies were commodities to be molded, surveilled, fetishised or made the butt of the joke, that sexual power, which might give some fleeting leverage, was the only power worth having. This lie curdled the emerging promise of 20th-century feminism, and as our ambitions shrank, the potential for exploitation grew.

And she identifies

the rise of easy-to-access hardcore pornography, which “trained a good amount of our popular culture,” she writes, “to see women as objects – as things to silence, restrain, fetishise or brutalise. And it’s helped train women, too.”

But while Gilbert is unsparing in her descriptions of pornography’s warping effect on culture and its consumers, she’s curiously reluctant to acknowledge what seems obvious: porn hasn’t been good for us. While her descriptions of the cultural landscape imply that the mainstreaming of hardcore porn has been a bad thing, she pulls her punches.

“I’m not interested in kink-shaming,” she writes, “and I’m not remotely opposed to porn” – immediately after describing a 2019 study that found that 38% of British women under 40 reported having experienced unwanted slapping, choking, gagging or spitting during sex.

And that’s the typical approach. Identify the problem – and completely deny the obvious solutions or necessary acknowledgement that yes – porn does untold harm.

The NYT article continues

Despite significant evidence that a deluge of pornography has had a negative impact on modern society, there is a curious refusal, especially in progressive circles, to publicly admit disapproval of porn.

Criticising porn goes against the norm of nonjudgmentalism for people who like to consider themselves forward-thinking, thoughtful and open-minded. There’s a dread of seeming prudish, boring, uncool – perhaps a hangover from the cultural takeover that Gilbert so thoroughly details. More generously, there’s a desire not to indict the choices of individuals (women or men) who create sexual content out of need or personal desire or allow legislation to harm those who depend on it to survive.

Exactly. The ‘inclusive’ ‘diverse’ sexual message of anything goes and there are no sexual morals or standards – even if there is harm – is a typical libertarian and a typical left approach.

That’s why I say that political parties that are libertarian – such as ACT Party now – are fiscally conservative but they’re not morally conservative. The ACT party used to be socially conservative but not now. Their vote on virtually all moral issues – abortion, euthanasia, gender ideology, LGBT issues, definition of marriage, conversion therapy bans are no different to the votes from the radical left parties.

The article continues – and here’s the key bit

But a lack of judgment sometimes comes at the expense of discernment. As a society, we are allowing our desires to continue to be moulded in experimental ways, for profit, by an industry that does not have our best interests at heart. We want to prove that we’re chill and modern, skip the inevitable haggling over boundaries and regulation and avoid potentially placing limits on our behaviour. But we aren’t paying attention to how we’re making things worse for ourselves. Phillips’s case is one example of how normalisation of pornographic extremes has made even lurid acts de rigueur; it’s not hard to imagine a future that asks (and offers) more than we can imagine today.

Most recently, the only people who seem willing to openly criticise the widespread availability of pornography tend to be right-leaning or religious and so are instantly discounted – often by being disparaged as such. But cracks are beginning to appear in the wall, as shown by sources as varied as the recent, if quiet, revival of the anti-porn feminist Andrea Dworkin (Picador books rereleased a trio of her most famous works this winter) and the heartfelt podcasts of Theo Von, who frequently discusses his decision to stop watching porn.

It's an interesting admission, isn’t it.

It was right-leaning or religious people who were calling out the harms of pornography – but nobody wanted to listen.

But we were right! We’ve been proven correct over our concerns.

The radical left and libertarians are only now connecting the dots.

The article concludes

And members of Gen Z seem more willing to openly criticise it than their careful elders. The Oxford philosopher Amia Srinivasan, whom Gilbert quotes in the introduction to Girl on Girl, notes this in her 2021 essay “Talking to My Students About Porn”: “Does porn bear responsibility for the objectification of women, for the marginalisation of women, for sexual violence against women? Yes, they said, yes to all of it.”

It’s exactly what we said when we presented the petition back in 2017 calling on politicians to investigate the public health effects and societal harms of pornography. It had more than 22,000 signatures.

We said

“Social scientists, clinical psychologists, biologists and neurologists are now beginning to understand the psychological and biological negative effects of viewing pornography both online and through the media and video games. They show that men who view pornography regularly have a higher tolerance for abnormal sexuality, including rape, sexual aggression, and sexual promiscuity. Prolonged consumption of pornography results in stronger perceptions of women as commodities or as “sex objects,

Pornography has a damaging effect on intimacy, love, and respect and at its worst, leads to sex role stereotyping, viewing persons as sexual objects, and family breakdown. Research has also shown that children who are exposed to pornography develop skewed ideas about sex and sexuality, which lead to negative stereotypes of women, sexual activity at a young age, and increased aggression in boys.

At the time, the deputy chief censor called for the government to put more options on the table for regulating online pornography, saying

“Given New Zealand’s acknowledged problems with sexual and family violence and the demonstrated harm caused by pornography that degrades, dehumanises and demeans people (particularly women), the choice for Government and regulators, must be about how far we are willing to intervene — rather than whether we are prepared to intervene at all.”

What did the politicians do in response to our petition?

Zilch.

If we want to tackle sexual violence, we must first admit the role that pornography plays and the harm that it does to attitudes and actions.

This is from just two weeks ago on Radio NZ:

New Zealand has rates of sexual violence against teenagers above the global average, ahead of even a badly afflicted Australia, according to new research. A study published in The Lancet took a look across more than 200 countries over the last three decades. Among people aged 12 to 18, it estimated almost 30 percent of New Zealand women and one in five men experience sexual violence. The global rate was 18.9 percent for women and 14.8 percent for men.

So the global rate is 19% for girls but in NZ it’s 30%

The global rate is 15% for boys but in NZ it’s 20%

Shocking.

It's not rocket science, is it, that there is a moral aspect to sex and how we behave and treat each other – because it’s biblical Truth.

Pornography harms, and porn is a public health crisis rather than a private matter.

When even left wing media start calling it out, you know that perhaps we have finally reached a cultural tipping point.

The next time you get criticised for having a viewpoint consistent with biblical principles but opposed to the cultural viewpoint – don’t back down.

Our confused culture needs Truth more than ever.

Pornography is filmed rape.

American Greatness has a fabulous (harrowing) article on the harms of porn. It was written in 2019; imagine how much worse it's got now.

https://amgreatness.com/2019/12/15/a-science-based-case-for-ending-the-porn-epidemic/ The way 'sex work' is paid rape. The harms far outweigh any free speech bs imo.